A few lessons from reading: 2017-2025

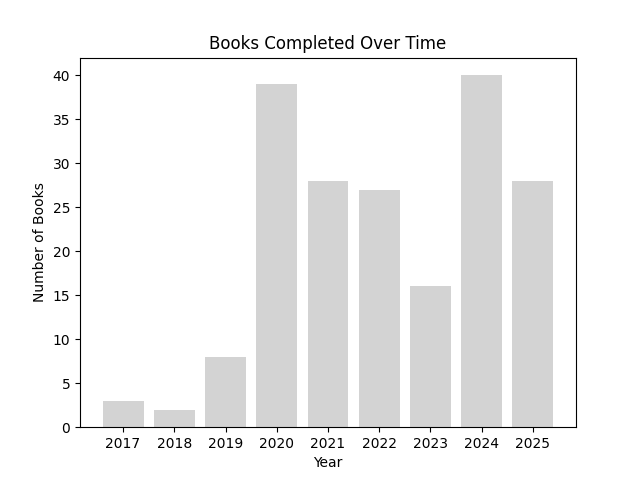

I started reading books seriously in 2020. It was hard to figure out which books to start with, so I began with those that were popular. Some of these were far beyond my reading level (i.e., The Brothers Karamazov and Atlas Shrugged), while others felt useful at the time but, in hindsight, were not at all substantive (i.e., self-help books and anecdotal non-fiction). Since I started tracking books, my reading output has been as follows:

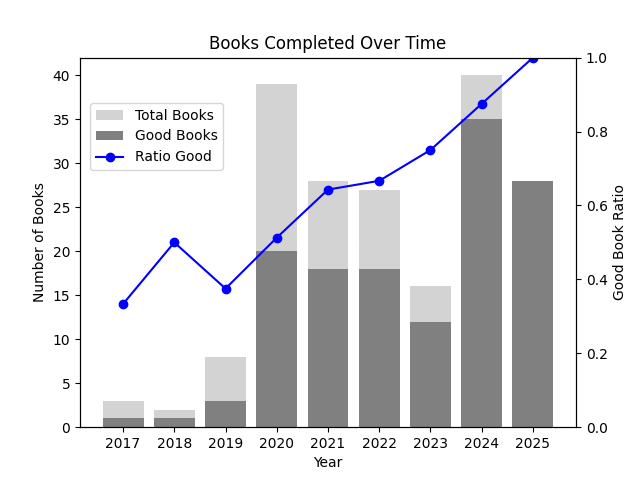

As you can see, my book count jumped considerably in 2020 and stayed at around 25-30 books per year. The jump in 2020 was when I realized that most of the successful people I admired read a lot of books and, thanks to the pandemic, I had a lot of time on my hands. I knew that I should be reading more, even though I wasn’t sure why, so I decided to track books as a reward signal to optimize for. However, the peak in 2020 looks less impressive once we analyze the quality of each book. If I use the simple qualifier “Would I recommend this”1, the trend looks as follows:

Notably, the ratio of good books to total books is increasing over time. Though part of this increase is due to recency bias, it can also be explained by the fact that I started quitting bad books earlier. For example, in 2024 I intentionally quit four books early, and in 2025 I skimmed through two subpar ones and quit another. Despite the content of many of those early books being somewhat unremarkable, the time I spent reading them wasn’t wasted; getting the reps in helped me improve my reading skills, develop my taste, and understand the literary landscape. Moreover, it helped me realize that what I value most about reading is its ability to update my world model, allowing me to see how certain ideas connect with the greater web of human knowledge.

For example, last year I read Anna Karenina (1878), in which the emancipation of the serfs is a notable discussion point among the characters. Then earlier this year I read Dead Souls (1842), which, beyond helping define the style of Russian realism that inspired Tolstoy (1828–1910) and Dostoevsky (1821–1881), satirically portrayed peasant life in pre-emancipation Russia. I was surprised to learn that the abolition of serfdom in Russia (1861) preceded the abolition of slavery in America (1865), and that both of these events came after the inventions of the photograph (1826) and telegraph (1837), and coincided with the publication of The Origin of Species (1859), and the inventions of the telephone (1876) and the lightbulb (1879). When I read The Brothers Karamazov (1880) a few years back, I didn’t fully grasp its historical context and imagined a world far more antiquated than was likely intended. That caused me to not only misunderstand the story, but also the cultural context in which it was written. Each milestone in history, whether an invention or reform, good or bad, is the product of a society’s culture. We can learn its facts through history books, but novels show us what the people themselves thought was important, even if only implicitly through their biases, settings, and stories. If we wish to predict the ramifications of our own culture, it is imperative that we look into the minds and stories of the past.

Another thing I learned from reading these past few years is how frequently I have misunderstood what a subject is really about, particularly those I dismiss as boring or uninteresting. In fact, I’d venture that nearly all popular topics are far more interesting and complex than you’d initially expect. I recently had this experience while reading A Concise Introduction to Pure Mathematics. I’m not sure I can describe what I thought pure math was about prior to reading it, but I now see that it’s largely about proposing rules and figuring out what their consequences are. It’s less about solving math problems directly and more about exploring the structure of a rule’s implications that, if we’re lucky, will uncover solutions to outstanding problems as well as those not yet put forth. In fact, one could argue that this is exactly how science works too, just replace the structure of mathematics with the fabric of reality. Scientists make conjectures about the world, verify them through experiment, and then figure out what their discoveries imply. Occasionally, these lead to radical changes in our understanding of the world that then open up powerful technologies like atomic energy and biotechnology, fields which were inconceivable prior to their scientific underpinnings. It is unfortunate that the modern scientific ecosystem relegates the role of basic and theoretical research to the sidelines in favor of goal-directed science, even despite its demonstrable success.

Likewise, I used to think of history as a collection of dry, immutable facts. Last year I read The Ancient City (1864), in which the author proposes a synthesis of ancient Greek and Roman society very different from the one I imagined, based entirely on primary sources. This, and similar books, caused me to realize that history is somewhat like a natural science: you’re documenting and understanding a foreign system that you cannot study directly, but only through the noisy traces it leaves behind. Just as in science and mathematics, historians conjecture hypotheses, figure out their implications, and decide whether to accept or reject them into the standard canon of knowledge. In another parallel, evolutionary biology and phylogenetics are highly akin to history, except that their data sources are present-day DNA instead of present-day documents. Each reconstruction of the past, whether it’s an ancient society or an ancestral organism, is a model built using a set of assumptions on the evidence we have today. After a certain point, all fields begin to look the same, or perhaps better expressed by Richard Feynman, “Nature uses only the longest threads to weave her patterns, so each small piece of her fabric reveals the organization of the entire tapestry”.

Upon beginning writing this essay, I’ve realized that while logging books I fell prey to Goodhart’s Law; tracking completions incentivized me to read short and easy books to bump the numbers up. It also caused me to read from start to finish which, while necessary for novels, is less important for non-fiction. That meant that if I were to read a single interesting passage in a large tome, it wouldn’t “count” as a completion even though I might have gotten more out of that one passage than from other full-length books.

It’s clear that something needs to change. It’s fine to track books, and I will continue to do so, but it cannot be the sole focus of optimization. Reading changes my model of the world, so I should be optimizing the extent to which each book improves it. While this is not measurable directly, a better world model plausibly leads to better ideas that can be expressed in forms like scientific projects and writing, which are measurable. I already publish scientific articles, but I haven’t published essays despite writing them occasionally for friends to read. So I’ll start posting essays online to once again instill a reward signal for reading, this time implicitly optimizing for the quality of books over their quantity.

And this blog, Conjecture, is where they will be.

I created this blog in 2022, and this is my first post more than three years later. What sparked it was a burst of inspiration from seeing my friend Aaron Feller launch his Substack, Latent Spaces. I originally wanted this to be a place for polished long-form essays only, but I’ve since realized that publication is more important than perfection. The focus here on Conjecture will be intellectual observations and ideas I’m working through that aren’t immediately related to my scientific research.

Thanks to Daniel Shea, Daniel Winkler, and Francesco Vassalli for reading drafts of this.

Thanks for the shout out! Loved the post and looking forward to the next.

What is your reading routine / schedule? Before bed? During commute? Dedicated time on the weekends?